German voters may soon be handed the opportunity to elect a new federal government following Wednesday’s late-night collapse of the federal coalition.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz (SPD) fired his FDP coalition party leader Christian Lindner as finance minister before holding a press conference from the Federal Chancellery during which he emphasized the need for a “government capable of acting” to manage the country’s pressing financial challenges.

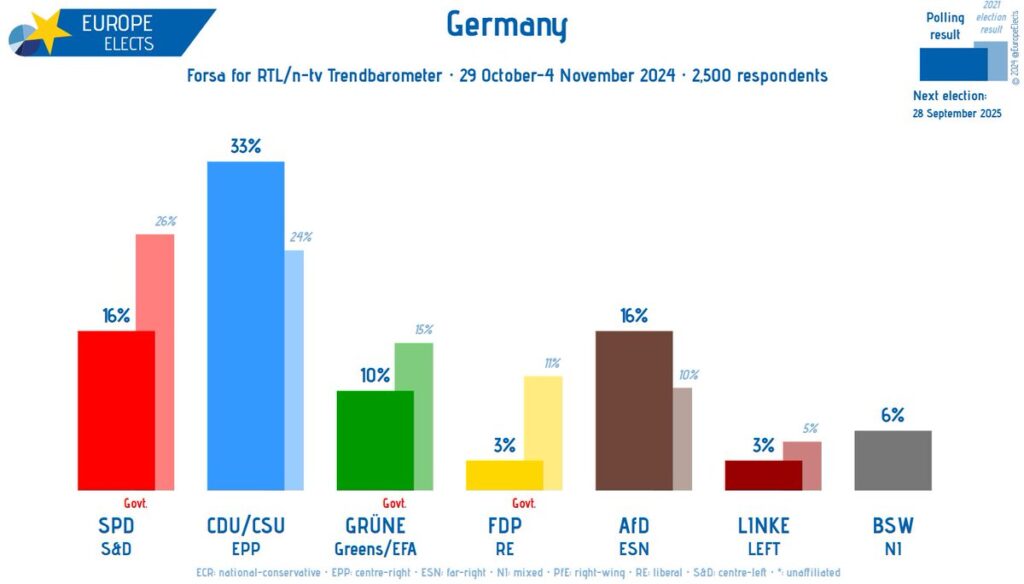

The latest polling from Forsa conducted this week makes for interesting reading should a snap election be called.

It shows the opposition center-right CDU/CSU bloc winning the most votes with 33 percent, followed by the incumbent Socialist Democratic Party (SPD) and the right-wing nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD) in joint second with 16 percent.

The SPD would plummet by ten percentage points from the 26 percent it attained in 2021, while its coalition partners, the Free Democratic Party (FDP) and the Greens would also both suffer significant losses — the FDP would drop from 11 percent to 3 percent while the Greens would be knocked down to 10 percent from 16 percent.

Similarly, the Left party would drop from 5 percent to 3 percent. Some of that support will be siphoned off in favor of the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), whose namesake split from the Left earlier this year to form a new party that is currently polling at 6 percent.

Another poll from Insa for the Bild newspaper puts the AfD a touch higher at 18 percent, the CDU/CSU a click lower at 32 percent, and the FDP teetering on the edge of the threshold at 4.5 percent.

So what could this mean for a new government?

The first thing to note is that German governments are nearly always coalitions due to the country’s electoral system. The last time a political party won an outright majority was in 1957 when the CDU/CSU secured 50.2 percent of the vote.

The second caveat on any hypothetical situation regarding the parliamentary arithmetic is the fact that parties in German federal elections typically need to surpass the 5 percent threshold of votes in order to sit in the Bundestag — a feat neither the Left nor the governing FDP will reach based on the current polling.

One important exception to this is if a party wins three or more direct seats in the first-past-the-post element of the election. In 2021, the Left entered parliament by securing three direct votes, even though they fell beneath the 5 percent threshold. The FDP, however, did not win a single direct seat but qualified for parliamentary representation by winning 11.5 percent of the vote.

With the FDP’s popularity plummeting, for this exercise, we will assume the party does not enter the parliament and therefore cannot be involved in coalition talks. We will assume that the Left’s concentrated support could see it enter the Bundestag under what is called the “basic mandate clause.”

In this hypothetical situation, several coalition scenarios could emerge.

CDU/CSU + SPD

Despite polling showing a CDU/CSU-SPD coalition wouldn’t reach the magic 51 percent, the redistribution of seats after votes for smaller parties who fail to reach the threshold are removed would likely see them attain a parliamentary majority on this polling.

As such, what is known as a “grand coalition” between Germany’s historically two largest parties could potentially be formed once more, a scenario that has occurred multiple times in the post-war era.

This could be problematic politically for the CDU/CSU who have just spent the last four years bashing the governing party, but could potentially justify the move to its voters by the fact it would be the dominant coalition partner. Such a move would be a risk and could potentially result in disillusionment from those fed up with the same old establishment parties and push supporters to the fringes.

CDU/CSU + SPD + Greens

The CDU/CSU could bring in the Greens to try and work together in order to phase out the Alternative for Germany (AfD), the right-wing anti-immigration party that Germany’s mainstream parties have deemed too unpalatable to work with at the state level.

However, this poses several challenges. First, both the Greens and the SPD would have just lost considerable support and the optics for the CDU/CSU of campaigning for change and winning the election, only to bring in two of the three current coalition parties back into power would be extremely damaging.

Second, such a broad coalition would inevitably face internal ideological differences, especially on social, economic, and environmental policies. Both the SPD and the Greens would likely demand significant concessions from the CDU/CSU to support their policies which would inevitably result in a watering down of campaign pledges.

The CDU/CSU would likely have campaigned hard on immigration to beat off competition from the increasingly popular Alternative for Germany, and any hardline stance would not be signed off on by either prospective coalition party.

The elephant in the room: The AfD

Another way to likely secure a working majority would be for the CDU/CSU to welcome in the AfD from the cold. If the “grand coalition” government did not materialize, the AfD would consider themselves to be in pole position to enter the federal government for the first time.

However, this is politics, and the most workable solution in theory rarely succeeds in practice. The CDU/CSU has consistently ruled out working with the AfD at the state level and the establishment parties seem intent on retaining an effective cordon sanitaire around the populist group for fear of giving it credibility.

Together, the CDU/CSU and the AfD would receive around half of the vote on current polling, likely enough for a potentially viable government after the redistribution of seats. It could potentially attempt to work with other parties on a case-by-case basis but a possible addition could be the BSW which at least aligns with the pair on socially conservative issues but differs wildly when it comes to the economy.

While a coalition between CDU/CSU, AfD, and BSW would technically command a comfortable majority, it is highly unlikely due to the AfD’s political isolation and considerable internal and external pressure among the CDU/CSU and BSW to reject any cooperation with the AfD.

Political stalemate

Should this polling hit the mark come the next federal election, the most likely scenario would be political stalemate and fresh elections, further paralyzing Germany at a time of economic instability and a fractious geopolitical climate with war in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Add into the mix that Donald Trump would have just re-entered the White House, the European Union could ill afford its largest economy to be so fragmented at a time when Brussels would be intent on showing its strength and standing tall in the face of the new Republican administration.