Havel’s corner, unveiled in Brussels on Tuesday, should be reminiscent of the legacy of the former Czech president and writer Václav Havel and at the same time entice people to sit and talk. Two chairs and a round table, through which a tree grows, stand in the park in sight of the European Parliament. According to the Czech Ambassador to Belgium, Pavel Klucký, the space can serve, for example, as a meeting point for citizens and politicians.

“We want it to become a real place where various ideas, often controversial, are expressed,” Klucký told reporters, according to whom the space, despite its small size, could become the Brussels form of London’s Hyde Park. Since the place is on the road leading to the meeting place of seven hundred politicians, it could serve the purpose well.

The Czech Embassy in Brussels plans to revitalize the site by organizing some events, for example in connection with the upcoming Czech Presidency of the European Union.

Similar monument stands in Prague since 2014

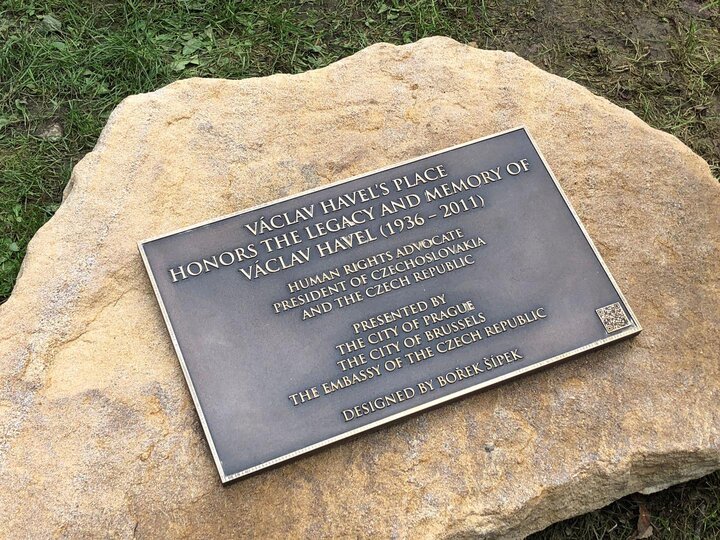

The monument, designed by Havel’s presidential architect Bořek Šípek, was created based on cooperation between Prague and Brussels’ City Halls. It is almost identical to the two chairs and table which since 2014 have stood as a commemoration of the tenth anniversary of the Czech Republic’s accession to the EU on Maltézské square in Prague.

Brussels Mayor Philippe Close noted that the Belgian capital is becoming another place where Šípek’s works are installed. According to him, Havel’s corner should cultivate the skills of debate and dialogue.

Close recalled that Havel had already received an honorary doctorate from ULB university in Brussels in 1991, and in 2009 he delivered a speech in the European Parliament calling for pro-European ideas. “Europe is the home of our homes,” Close quoted Havel as saying.

The mayor of Prague, Zdeněk Hřib, recalled that Havel was present at the birth of the Visegrad Group, the purpose of which was to promote democracy in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and Hungary, along with their full integration into the EU.

“Three decades later, however, it looks as if this project has turned into something quite different,” Hřib said, referring to developments in Poland and Hungary that are in conflict with EU institutions due to tendencies to reduce the independence of the judiciary or the media. According to Hřib, Havel’s ideas have not disappeared and can inspire Central Europe and its surrounding states in this day and age.