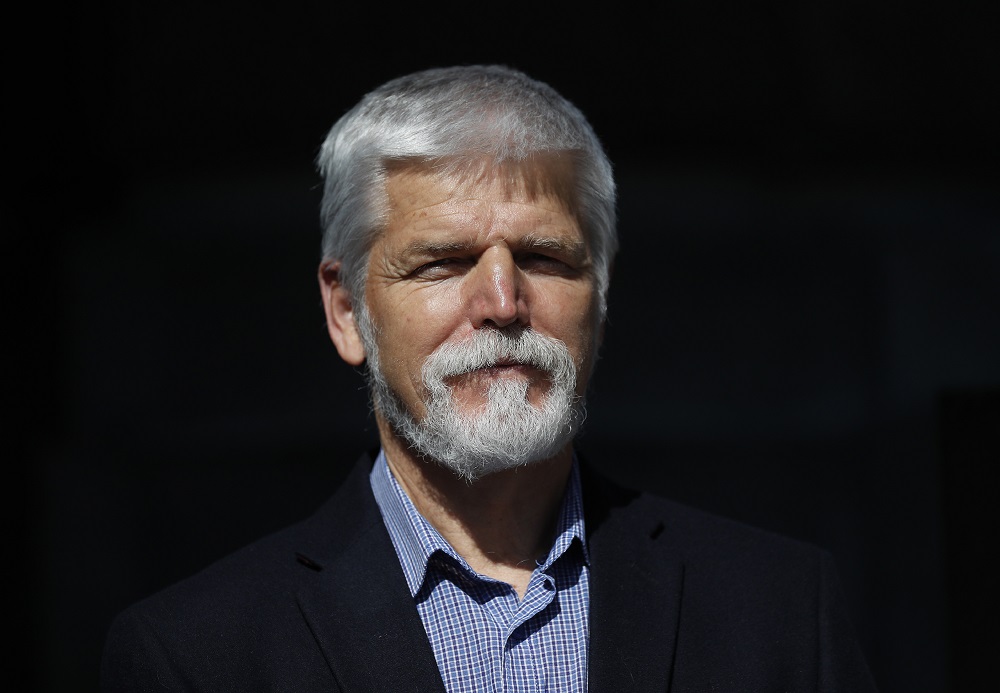

Newly elected Czech President Petr Pavel has dismissed the Visegrád Group (V4) as little more than a “consultation forum” in his latest remarks about the future of the alliance.

Speaking from Slovakia during his first trip abroad as Czechia’s premier, Pavel continued to present a lukewarm attitude toward the political alliance between Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland.

While claiming the V4 has not been effective recently, he refrained from stating he would seek to withdraw from the group; however, he claimed there is no longer a clear political alliance among members.

“Nowadays, I perceive the V4 more as a consultation forum without the ambition of detailed coordination on foreign or security policy. The Visegrád Four does not serve that purpose,” Pavel told reporters.

[pp id=68249]

He suggested that on this basis, as a loosely aligned group of nations, in his view the V4 could seek to include additional voices such as among the Baltic nations, where closer economic and commercial ties could be discussed.

Pavel’s dismissal of the group as a political alliance is the latest blow to the V4 founded more than three decades ago in 1991. The Czech president’s predecessor, Milos Zeman, was a staunch advocate of the alliance. Pavel’s electoral success looks set to see Czechia further drift apart from members such as Hungary, as the two governments hold polarizing views on their approach to the conflict in Ukraine.

“Hungary has been going its own way for a long time,” Pavel said last month, adding that if the V4 members cannot agree on basic issues, “it is a fundamental problem” for the future of the group.

[pp id=67629]

In a recent interview with German newspaper Die Zeit, Pavel showed his contempt for the Hungarian government, which “is taking a fundamentally different course toward Russia,” and for Poland, which has been “criticized for its handling of the rule of law.”

He claimed the “Visegrád alliance is in crisis,” but suggested changes in government within Hungary and Poland could bring them back in line with his values.

“Many democratic states have gone through phases of democratic deficit throughout their history, so I wouldn’t see it as tragic. Prime ministers and parties can be voted out,” he told the newspaper.