Germany faces a looming energy crisis as the surge in demand from massive new data centers, driven by the artificial intelligence (AI) boom, is quickly outstripping the capacity of its existing electricity grid. This is the urgent warning from seasoned energy manager Andreas Schierenbeck, CEO of Hitachi Energy, in a recent interview conducted with Welt newspaper.

Schierenbeck, who has held leadership roles at Siemens, ThyssenKrupp Elevator, and Uniper, stresses that Germany’s current energy plans are insufficient to cope with the unprecedented energy appetite of modern data centers.

“We must not overlook the coming boom in data centers,” Schierenbeck warns. “Just two or three additional data centers can massively increase energy demand – and Germany is not yet prepared for this.”

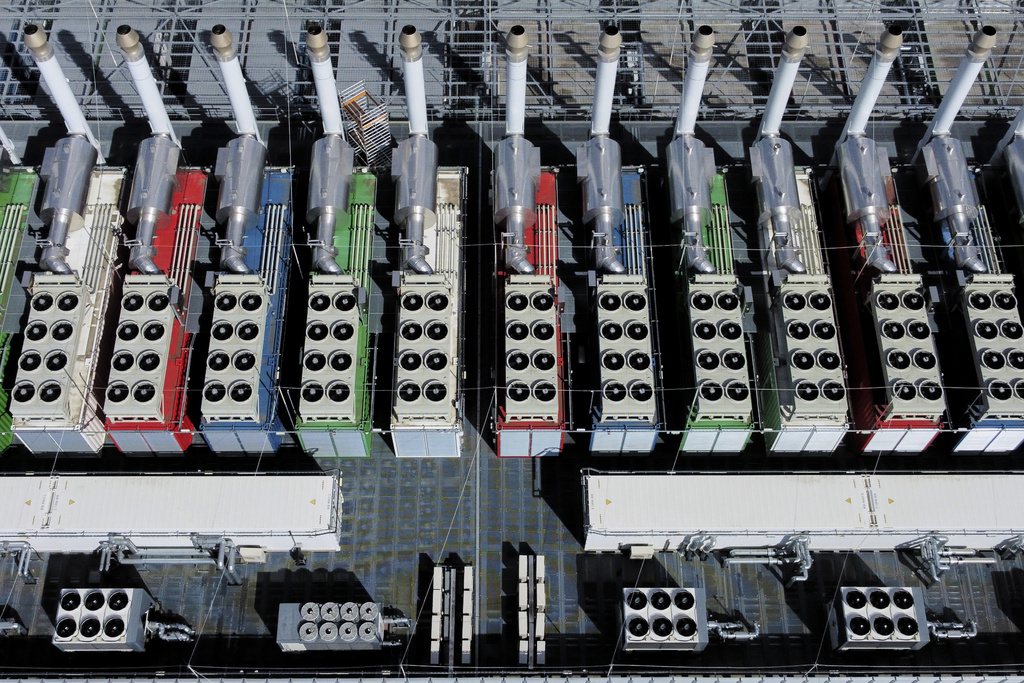

The scale of new data centers is fundamentally changing energy planning for the German state, which has moved away from reliable nuclear power and fossil fuels. Schierenbeck points out that standard data centers used to require 10 to 20 megawatts (MW). Today, facilities are being planned for 200, 500 MW, or even more than one gigawatt (GW)—”i.e., the size of a large coal-fired power plant.”

This rising consumption threatens to widen Germany’s existing energy deficit. After the nuclear phase-out and the scaling back of coal, Germany has transitioned from being a net exporter to a net importer of electrical energy.

“Germany is in a power gap – and it is threatening to grow,” Schierenbeck says.

Schierenbeck emphasizes that a reliable electricity grid, when using renewables like wind and solar, can only achieve a “maximum of 70 to 80 percent stability.” Beyond that, a secondary, stable energy source is required. While France uses nuclear power and Norway uses hydropower, he suggests the German approach of planning gas power plants for peak loads and during so-called dark lulls “is entirely sensible.”

However, even with the right energy mix, the network itself is becoming a severe bottleneck. The penalty for slow grid expansion is steep: “If our electricity network is not powerful enough, no industry will settle there.”

Data centers are already reaching their limits because “there are hardly any locations with an available network connection,” a critical point for planning, he stated.

Adding to the capacity issue are bureaucratic hurdles, particularly concerning grid connection approvals. Schierenbeck criticizes the current “first-come, first-served principle” for connection applications, which he calls the “greyhound principle.”

“Due to the greyhound principle in permits, many connection points are actually blocked – for example by battery storage projects that are three times oversubscribed. This often doesn’t make technical sense, but whoever comes first will be served first,” he explains, adding, “To be clear, there is no prioritization today. Today we are working through.”

Schierenbeck proposes that the regulatory process must evolve to consider the broader public benefit. He advocates for prioritization based on investment criteria, suggesting it should matter “how much is invested in the location for the grid connection, how many jobs are created and how grid-friendly the project is.”

Beyond grid capacity and regulation, the energy transition faces a tangible manufacturing challenge: a global shortage of transformers. Without a reservation, the waiting time for a transformer in Germany can be up to four years.

“The shortage is a fact. It will continue for several more years. Transformers have become the bottleneck of the energy transition,” he states.

The issue stems from a lack of investment security, as “For a long time, demand was difficult to predict; many customers were unwilling to reserve capacity or enter into framework agreements.” Now, with customers planning and reserving long-term, companies like Hitachi Energy are gaining the security to invest in new manufacturing capacity, such as at their Bad Honnef plant.

Furthermore, he suggests that production speed is hindered because “Today, almost every transformer is unique.” To speed things up, Schierenbeck suggests a move “away from one-off manufacturing and towards more standardized solutions.”

Other bottlenecks include materials, like electrical sheet, of which Europe produces only about 35 percent of its own requirements, and the scarcity of specialist companies needed to build the massive, high-capacity transformer plants.

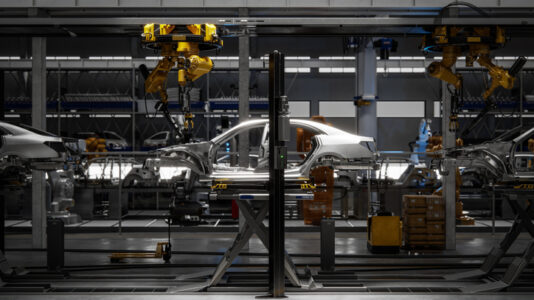

Comparing Germany to the U.S., where Hitachi Energy operates a large market, Schierenbeck notes that the U.S. benefits from faster decisions and implementation:

“Data centers are built quickly and network connections are allocated quickly.”

He concludes that catching up with countries like China in manufacturing capacity will be a monumental task, likely taking “not just years, probably decades.”