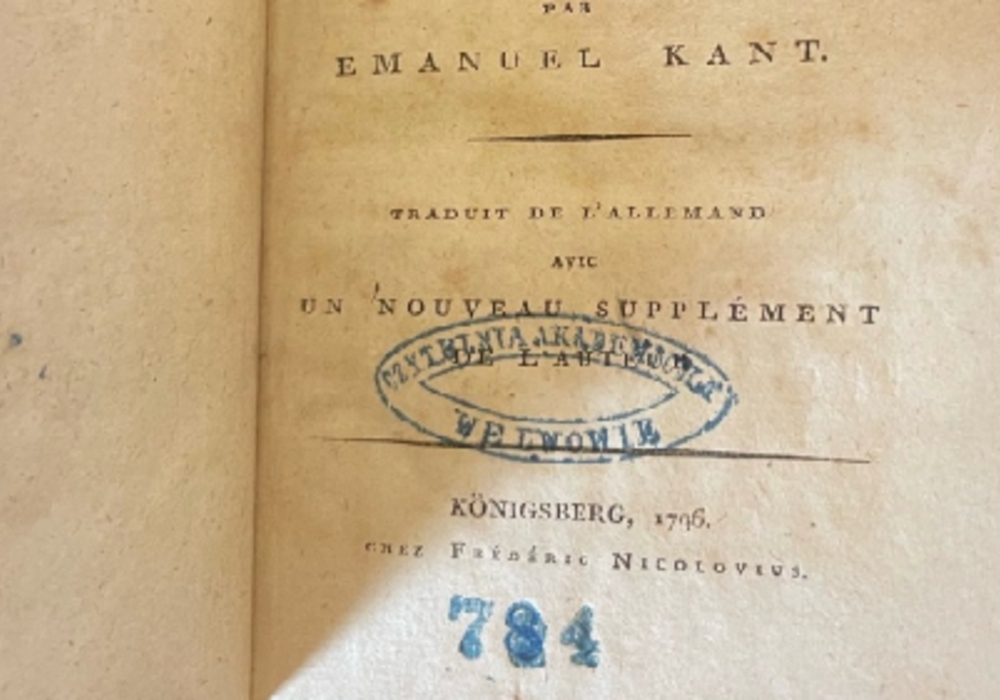

President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to gift Pope Francis with the first, 1796 edition of Immanuel Kant’s “Perpetual Peace” was a poor one.

While Macron could not be expected to understand the implications of his gift, at least someone from his political team could have taken a moment to reflect why it featured a stamp in Polish which read: “Academic Reading Room in Lwów.” Whether it was acquired legally, or stolen, especially because many of the book collections and pieces of art in Lviv (Lwów in Polish) were subject to plunder for decades.

So, the French president should have considered whether a book with such a stamp was the best choice as a gift for Pope Francis.

After all, Macron’s sensitivity to stolen art cannot be disputed. In 2021, he said during the France-Africa summit in Montpellier that 26 pieces of art stolen in the 19th century were to be handed back to Benin. Works of art located in France will also be returned to the Ivory Coast as restitution for stolen artwork from Africa, with Macron saying it was “one of the most important points of the new relations with countries of Africa.”

If Macron is so sensitive about works of art and various artifacts plundered by France in its previous colonies, then he should be even more sensitive about something that could have been plundered from Polish Lwów during the Austrian partition or during World War II. At the very least, it should be verified whether the work is listed in the registry of stolen cultural goods, and if so, then maybe it should simply be given back.

It is possible that the rare edition of Kant did not arrive in France illegally, but it seems highly inappropriate to choose this book in particular as a gift to the pope.

Every educated leader should know how many book collections were lost by Poland during wars, partitions, and the occupation, and the chance of fencing a stolen item, even unintentionally, is high.

Additionally, leaders typically choose to gift items that are the work of their citizens and institutions —something that is synonymous with the state of the donor. The work of the German Kant from the collection of a Polish Academic Reading Room in Ukraine’s Lviv fails to meet these criteria.