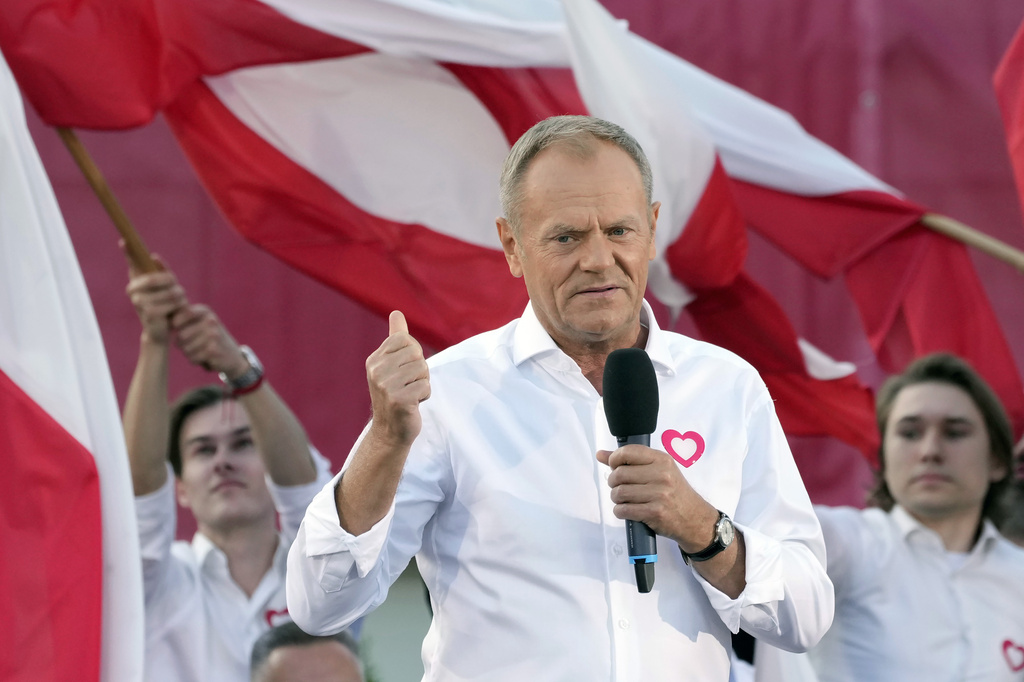

Last week, as the European Parliament embraced the new migration pact with support from the European People’s Party (EPP), which includes Poland’s Civic Platform (PO) and co-ruling PSL, Prime Minister Donald Tusk voiced strong dissent against the pact.

He declared: “As far as the position of the Polish government is concerned, there will be no consent or acceptance of any compulsory migrant relocation mechanism.”

Tusk further asserted that “Poland will not accept illegal immigrants under any such mechanism.”

However, even Poland’s opposition during the EU Council’s adoption of the pact will not prevent it from coming into effect. At this stage, creating a blocking minority is no longer feasible, especially since the pact’s endorsement is driven by the EU’s largest countries and major political groups, including the EPP.

Thus, Tusk’s declarations in Poland about rejecting the migration pact are pure hypocrisy and an attempt to mislead the Polish public.

Echoing his migration stance, Tusk’s assurances about rejecting immigrants are reminiscent of his election campaign promises about fuel prices. Last week, shortly after a government meeting, when asked about his earlier campaign pledge to lower gasoline prices to 5.19 zlotys (€1.22) per liter — a stark contrast to the current price of around 7 zlotys (€1.64) — Tusk unexpectedly stated, “I do not take responsibility for fuel prices, as that is not within the prime minister’s purview.”

Yet, during last year’s electoral campaign for the Sejm and Senate, he repeatedly told his supporters that if he were prime minister, gasoline would cost 5.19 zlotys, and electricity and gas bills would be half of what they are now. He implied that a prime minister could decisively influence not only fuel prices, but also the cost of electricity and gas in a way that binds the companies involved in their production and distribution.

As with his fuel price promise, Tusk’s pledge to refuse immigrants may follow a similar trajectory.

Now, as the campaign for the European Parliament elections begins, he assures that Poland will not accept immigrants. However, post-election, he is likely to concede that Poland must show solidarity with other EU countries and participate in the distribution of immigrants.

This pattern of pre-election promises versus post-election realities casts a shadow on the sincerity and feasibility of Tusk’s commitments, raising questions about the true extent of a prime minister’s influence over national and EU policies.