The recent European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) survey, which concerned the 12 leading EU member states, has revealed highly worrying trends for the future of integration.

The financial crisis from 10 years ago divided the EU into the poorer south and the wealthier north, while the 2015 migration crisis divided the union into the immigration restrictionist east and multicultural west.

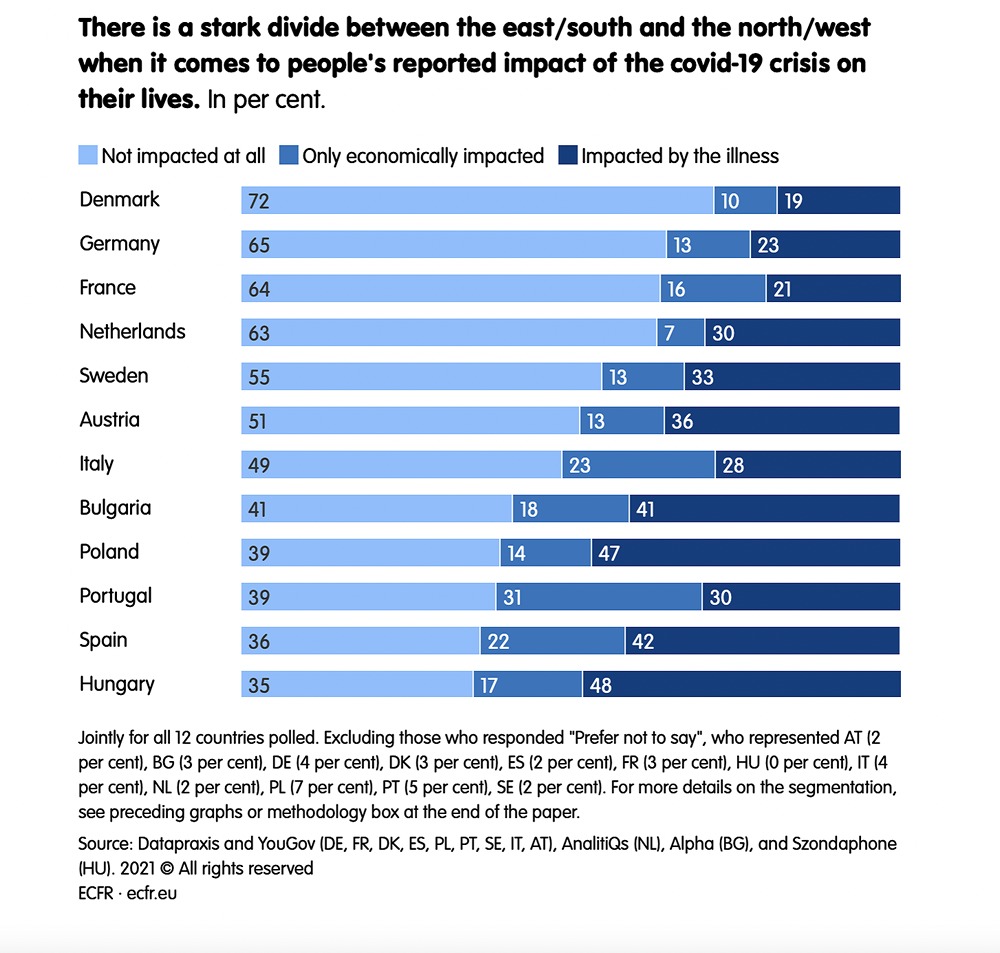

It turns out that the pandemic has also created divides, yet even more severe and deep ones. On one side there is the EU’s south and east, where the majority of respondents believe that the pandemic affected them personally, be it health-wise or economically. Yet, in the north and western parts of the EU, the majority of the citizens looked at the pandemic as a kind of macabre spectacle which did not concern them.

While only 39 percent of respondents in Poland believe they left the pandemic unharmed, 47 percent stated they felt its health consequences, and 14 percent that they were affected economically. Meanwhile, in Denmark, 72 percent said they did not feel affected, and only 19 percent felt the health consequences, and 10 percent the economic ones.

An additional division is also present: the generational one. It is commonly thought that the elder generations paid the highest price during the pandemic, as they were the most at risk from the virus. Yet, the ECFR survey shows a different picture. It refers to factors that are often neglected: for many people aged 60 and above, their economic situation and their lifestyles have not changed.

This is different for youth who felt the restrictions imposed by the government very severely. Not only were they stripped of their feeling of freedom, but also of their income.

In the group of EU citizens aged up to 30, 57 percent of them agree that the aim of the lockdown was to stop the pandemic. Yet, already 20 percent think that it was a secret government plan to subject societies to greater control and 23 percent believe the affair was about hiding authorities’ incompetence.

These three views can also be found among people aged 60 and above, but in entirely different proportions: 71 percent believe the aim of the lockdowns was to stop the pandemic, 14 percent believe in a “secret plan”, and 14 percent believe the lockdowns were aimed at hiding government incompetence. Among all the EU citizens, 64 percent believe in their government’s good intentions but 36 percent do not (19 percent accuse them of incompetency and 17 of secret plans).

Behind this average, huge differences between EU countries are hidden. The highest charge of distrust can be found in Poland, where only 38 percent of respondents trusted in the government’s good intentions, while 27 percent suspect that there was a secret scheme to strip citizens of their freedom. Another 34 percent believe the lockdown was meant to hide the government’s powerlessness.

Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, 76 percent do not have any suspicions towards their government, only 12 percent see a hidden scheme, and 11 percent the result of ineptitude in fighting the pandemic. Interestingly, France is much more similar to Poland in this case than Benelux or Scandinavia. Only 56 percent of French trust the central government when it comes to the lockdown, 24 percent saw a secret plan, and 20 percent ineptitude.

Where does this division come from? It stems from the scale of devastation caused by the pandemic. Those who paid for it with their health or wealth were much more likely to accuse the government of excessive, radical, or unfair actions.

What also compounds this is the scale of polarization on the political scene. Poland, but also France, entered the pandemic with a large part of society not believing in the necessity of government actions. The pandemic experience only deepened such feelings.

All of this portends a poor outlook for the EU’s political future. The survey’s authors pointed out that several populist parties such as the Germany’s Alternative for Germany (AfD) or France’s National Rally have begun to draw from libertarian programs and are hoping that they will rise to power or at least strengthen their influence on a wave of citizens suspicious of their governments’ motives.

The potential of for citizens’ frustration boiling into rage should concern European leaders.

While 64 percent of respondents felt fully free in the EU prior to the pandemic, only 22 percent think so today. Moods in Germany in particular are worrying, as 49 percent of Germans say that they feel stripped of their freedom (compared to 21 percent in Poland). The authors believe this to be a result of a democracy based on consensus in which it is rare to have open debates about the problems of citizens.

Moreover, 58 percent of Germans think that all sorts of institutions are responsible for the scale of the pandemic (starting with China and moving all the way to the European Commission’s issues with purchasing vaccines). Only 31 percent associate the pandemic with lack of discipline among citizens. Yet in the Netherlands, these values are almost completely reversed (31 and 63 percent, accordingly).

Given such differences in mentalities, it will be very difficult to maintain the EU’s cohesion in the upcoming years, the report’s authors warned.