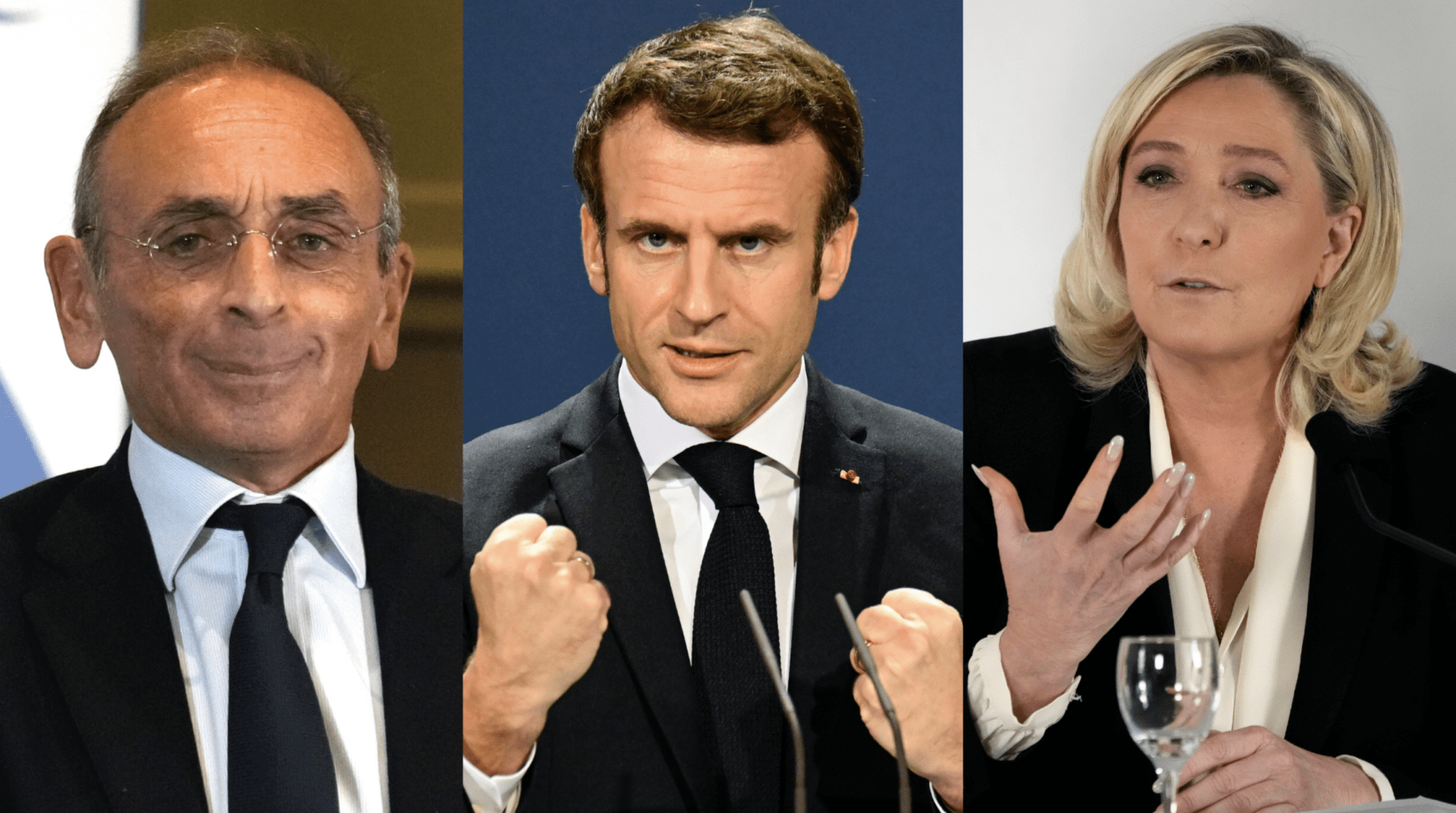

With two and a half months left before the first round of the presidential election and just a little over one month before the final deadline for would-be candidates to submit their endorsements to the French Constitutional Council, three candidates totaling over 40 percent of voting intentions in polls still have not reached the legal threshold of 500 signatures from elected politicians to support their candidacy. In theory, they could still be barred from standing in the election by the French establishment, as this is made possible by French law.

To be allowed to run for president of the French Republic, a candidate must be endorsed by a minimum of 500 mayors, MPs, MEPs, or departmental and regional councilors. The endorsements have to come from 30 different departments, and no more than one-tenth of a one’s endorsements can come from the same department. An elected politician can only endorse one candidate and his endorsement will be made public.

[pp id=26674]

This specificity of the French electoral system has made it more and more difficult for outsiders or so-called “populists” to take part in the presidential race. During Marine Le Pen’s previous attempts, she managed to obtain her 500 endorsements in the end but had to spend a lot of time and energy on this issue instead of focusing on her presidential campaign. Thus, even if Zemmour, Le Pen, and left-wing ‘populist’ Mélanchon eventually get their 500 signatures before the March 4 deadline, they will have been put at a disadvantage. Le Pen already had great difficulties getting her 500 signatures in 2012 and in 2017.

Apart from Éric Zemmour and Marine Le Pen, who are on equal terms with center-right Valérie Pécresse in the polls, and apart from leftist populist Jean-Luc Mélanchon, who is the best-placed candidate to the left of Macron, there is another right-wing candidate, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, who has also signaled that he might not be able to reach the legal threshold of 500 signatures. In 2017, Dupont-Aignan was the only candidate having failed to make it to the second round of the presidential election to support Marine Le Pen against Emmanuel Macron.

[pp id=23326]

Originally, the French system of endorsements needed to run for president was designed as an electoral screening rule meant to limit the number of presidential candidates, and in particular to avoid candidacies by people lacking seriousness or willing to run not to win the election but just to get a voice in the media for some cause. However, in 1976, the threshold was changed from 100 endorsements to 500 and later on rules were again tightened to make endorsements required from many parts of the country and then the rule was changed again to make all endorsements public, which is a very efficient way in a country dominated by the leftist-liberal media to deter left-wing or mainstream politicians who, for the sake of democracy, might consider giving their signature to a right-wing candidate from the other side of the “cordon sanitaire.”

The current rules actually make it possible for the ruling establishment to bar anyone who does not belong to the mainstream from trying his or her chances. The discussion about the undemocratic nature of these rules resurges before every presidential election. It would be quite easy to bring some flexibility to the process, for example by allowing an elected politician to endorse several candidates, so that an endorsement would not look like supporting a given candidate. However, neither Macron’s current parliamentary majority nor the previous ones have ever be willing to remove this significant roadblock to the democratic process.

This is all the more surprising that the French president himself was keen to present himself as a great defender of democracy during his Jan 19 speech before the European Parliament, whereas the possibility given to the ruling parties to exclude others from running for president is very undemocratic by European standards.

[pp id=5808]

Valérie Pécresse, the center-right candidate, has already gathered thousands of endorsements, and she is said to have instructed her party’s elected politicians not to endorse Marine Le Pen, for example, while Éric Zemmour has appealed to her to help him get his endorsements as it is in her own interest. Indeed, without Zemmour’s candidacy, Le Pen’s electorate would no longer be split and the threshold to make it to the second round would be raised back to well over 20% of the vote, which is a level of support utterly out of reach for Pécresse. With both Zemmour and Le Pen on her right flank, sharing a total of some 30 percent in the polls for the first round and with Macron at around 25 percent of voting intentions, even if Pécresse were to score 15 to 17 percent in the polls, she could get enough votes to be Macron’s contender in the second round of the April presidential election.

But the endorsements issue is not the only challenge that makes the French elections pretty undemocratic by European standards.

Although in France a candidate with at least 5 percent of the vote in the election gets his or her campaign expenses refunded by the state after the election, no French bank will lend money to Marine Le Pen or her party, the National Rally, for an electoral campaign. In the run-up to the 2015 regional elections, this had led Le Pen’s party, then named National Front, to turn to a Russian-owned bank to obtain a loan for their electoral campaign. This is how Marine Le Pen and her party earned themselves a reputation of being financed by Vladimir Putin, although the loan conceded by the First Czech Russian Bank was on commercial terms and its conditions were not particularly favorable by the market standards of the time.

To make things even more difficult for his main opponent in future elections, and knowing very well that French banks would not give loans to Le Pen and her party for political reasons, in October 2017 President Macron had his MPs enact a law that forbids French political parties from obtaining loans from banks with headquarters outside the European Economic Area.

[pp id=25482]

As one could read in the center-right newspaper Le Figaro just a week ago, Marine Le Pen now has to campaign with no money at all, which puts her at an additional disadvantage, and a very big one indeed.

Thanks to over 85,000 people having joined his brand-new Reconquest party, all paying their annual subscription fee on entrance, and thanks to a wave of donations, Le Pen’s most direct competitor Éric Zemmour does not seem to have this kind of problem. He even looks set to beat Macron’s previous record donation campaign dating back to the run-up to the 2017 presidential elections.

“Many contributors to Nicolas Sarkozy’s campaign in 2007, but also former financial supporters of Emmanuel Macron and François Fillon in 2017, have decided to help us,” Zemmour’s fundraising manager said to Capital at the beginning of January. The former journalist, who decided last year to enter politics out of his conviction that Marine Le Pen would never win, might not even need a bank loan for his campaign, and he will probably be the only one in such a situation among opposition candidates.

However, Zemmour has had to face a series of judicial trials on “hate speech” issues, which is nothing new to him, but never before had the judicial assault on him been so intense as since he announced his intention to take part in April’s presidential race. Among other cases brought against him, both old and new, on Jan 17, Zemmour was convicted for having supposedly incited “discrimination, hatred or violence against a group of people because of their origin or their membership or non-membership of a particular ethnic group, nation, race or religion.” This is because he once said on a C-News channel program he was hosting that since there are rapists and murderers among foreign unaccompanied minors who come illegally to France, France should not allow any illegal immigrants belonging to that category to stay on its territory. This, apparently, falls under France’s unique laws against freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

Clearly, France’s leftist-liberal establishment is not going to let someone like Le Pen or Zemmour win a presidential election without a fight, and with his current six-month EU presidency of the Council of the EU, Macron is too busy “defending democracy” against Poland and Hungary to bother about repairing democracy in his own country — and it just so happens that this stance is to his advantage.