Has any man spent more time in court than Italy’s Silivio Berlusconi and at the same time still walk away with so many acquittals? There are likely few contenders.

Italy’s former center-right prime minister’s latest acquittal came on Feb. 15. For Berlusconi, he has faced a Kafkaesque 86 lawsuits and over 4,000 court hearings without any condemnation except in all but one case where a judge later apologized to Berlusconi for having taken part in a politically-driven trial. In that one and only case, which led to Berlusconi being found guilty for alleged tax fraud in 2013, Cassation Court Judge Amadeo Franco said to Berlusconi in a private conversation how sorry he was for having taken part in a judicial farce which was “steered from above.”

The 2013 judgment made Berlusconi, the then main opposition leader, ineligible to run for office five years, and Judge Amadeo Franco’s confession, which had been recorded, was leaked in 2020, leading a former president of the European Parliament and leading member of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party, Antonio Tajani, to talk, with good reasons, of a judicial coup against Italian democracy.

[pp id=50064]

The same kind of judicial coup would have happened had Berlusconi been condemned in the “bunga-bunga” case. This case was at the center of an astounding 11 years of proceedings against Italy’s former center-right prime minister, who is currently an elected senator and the leader of Forza Italia, one of the three main parties forming the governing coalition together with PM Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia and Mateo Salvini’s Lega.

The Italian judiciary is notoriously dominated by left-wing judges and prosecutors and has been used by the left to fight its political opponents, as in the ongoing case brought against former Interior Minister Matteo Salvini for his decision not to allow the Open Arms ship belonging to a Spanish NGO to disembark its load of illegal immigrants in an Italian port in 2019.

On Feb. 15, however, Berlusconi was acquitted of bribing witnesses to lie about his “bunga-bunga” parties, almost nine years after having a seven-year sentence overturned by a court of appeal in the main case where he was accused of having had sex with a 17-year-old nightclub dancer.

[pp id=49966]

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni reacted to the news of Berlusconi’s acquittal saying it was “excellent news that puts an end to a long legal case that also had important repercussions on Italian political and institutional life.”

Infrastructure and Transport Minister Matteo Salvini said he was “happy for Silvio’s acquittal after years of suffering, insults, and useless controversies.”

“I was finally acquitted after more than 11 years of suffering, mud, and incalculable political damage, because I had the good fortune to be tried by judges who knew how to remain independent, impartial, and fair in the face of the unfounded accusations that had been leveled at me,” Berlusconi commented after his acquittal.

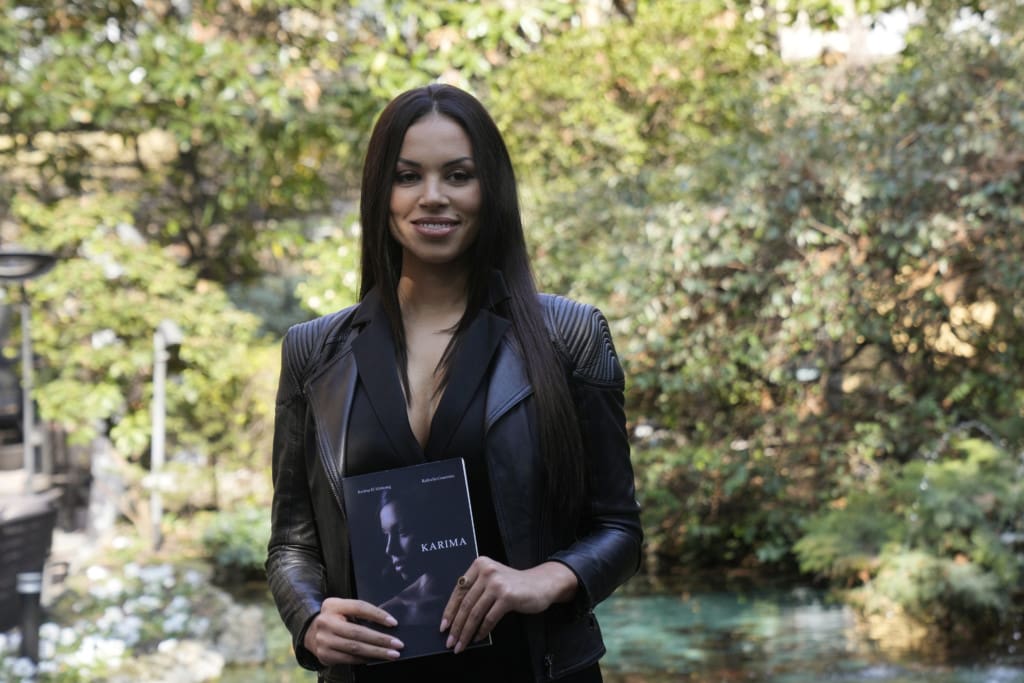

The main case which was brought to an end in 2014 when Berlusconi’s conviction was overturned on appeal concerned parties dubbed “bunga-bunga” parties by the media, that were held at the then prime minister’s private villa and attended by showgirls. The parties were revealed when Berlusconi intervened to have 17-year-old Moroccan nightclub dancer Karima El-Mahroug, nicknamed Ruby, released from police custody. The official name of the case brought against Berlusconi, whereby he was accused of having had sex with “Ruby” — something both Karima El-Mahroug and Silvio Berlusconi have always denied — is the “Ruby case.” However, the case which ended on Feb. 15 was called the “Ruby Ter case,” and both cases have often been referred to as one case, simply the “bunga-bunga” case, in the media.

Just after the Milan appeal court’s verdict, Italy’s Il Giornale newspaper described the inconsistencies in the Ruby Ter case in the following words:

“The first inconsistency was the underlying assumption that the witnesses in the first trial were divided into clear categories: those who said they had seen all kinds of things at Arcore [Berlusconi’s villa, ed.] were telling the truth, and those who remembered only dinners, jokes, and a few strips were lying. Such a division led to the indictment of all defense witnesses, even those who perhaps at the time of the alleged bunga bunga had already gone home, like poor Carlo Rossella [a journalist and CEO of Medusa film, a company belonging to Berlusconi’s Mediaset group, ed.] whom yesterday’s ruling fully rehabilitates. The second inconsistency was the absence of motive: if nothing illicit took place at those parties, it remains obscure why their host would have had to buy at great cost the silence and lies of the guests.”

Milan’s prosecutor Ilda Boccassini made her case not only against a former prime minister and the leader of the then opposition party, but also against guests who were among those invited to Berlusconi’s “bunga-bunga” party and a group of young women in their early twenties, with no knowledge of the law, who were pressured to make statements against themselves in the absence of their lawyers in violation of Italian law. This was one of the reasons invoked by the appeals court judge on Wednesday for his decision to dismiss the case made by the prosecution against Berlusconi.

[pp id=10966]

The leader of the Forzia Italia group in the Chamber of Deputies, Alessandro Cattaneo, said in an interview for Il Giornale on Feb. 16 that his party will now push harder for the creation of a parliamentary committee to investigate the political use of the justice system in Italy. With the center-right now in power, there is a good chance such an investigation committee will soon come to light and that could lead to a profound reform of Italy’s politicized judiciary.

“Eleven years of trial, more than 600 hearings, millions spent at the expense of taxpayers, a media, judicial and political pillory that calls for deep and structural justice reform for the protection of all citizens,” is how Licia Ronzulli, president of the Forza Italia group in the Senate, referred to the Ruby Ter case.

Started at an accelerated pace in October 2010, prosecutors and the Italian and international media presented what many guests called elegant dinner parties as some kind of orgy with prostitutes, which did a lot to tarnish the then prime minister’s reputation both at home and internationally. By doing so, it probably contributed to the fall of his government in November 2011. Based on the prosecutor’s assumptions against Berlusconi, the center-left Democratic Party (PD) called for Berlusconi’s “resignation and early elections” and asked for President Giorgio Napolitano to intervene if necessary. Like many members of the PD, Napolitano was also a former communist.

President Napolitano did indeed intervene. As early as June 2011, he was seeking out former European Commissioner Mario Monti to entrust him with the formation of a new government. It was then Monti who took the reins of the Italian government on Nov. 16, 2011, after several months during which the media reported frequent telephone conversations between President Napolitano, French President Nicolas Sarkozy, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

The whole sequence of events was described in a book published in 2017 by journalist Roberto Napoletano, former director of the news website Sole24Ore, entitled “Il Cigno nero e il Cavaliere bianco. Diario italiano della grande crisi” (“The Black Swan and the White Knight. Italian Diary of the Great Crisis”). In that book, former Italian Prime Minister and former President of the European Commission (from 1999 to 2004) Romano Prodi expressed his strong doubts about the interest rate spread crisis and the intense international pressure that Berlusconi’s government was subjected to in the months before his resignation.

According to Romano Prodi, the aim was to make Berlusconi pay for Italy’s positions in favor of Gaddafi, Putin, and Iran. Such an operation would probably not have been possible without the action of several debt rating agencies as well, which at the crucial moment lowered Italy’s rating without any real economic justification.

That thesis was not new at the time of the book’s publication, as it had already been supported by direct witnesses. For example, former Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Zapatero claimed in an interview with the Italian newspaper La Stampa in March 2015 that at the G20 meeting in Cannes on Nov. 3-4, 2011, Berlusconi and his economy and finance minister, Giulio Tremonti, were put under enormous pressure to accept an IMF loan they did not want to take, as they were keen to preserve their autonomous decision-making. According to Zapatero, “the United States and the advocates of fiscal austerity wanted to decide for Italy and replace the Italian government.”

In the book “Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crisis,” Timothy Geithner, who was U.S. treasury secretary from 2009 to 2013, says: “At one point that fall, a few European officials approached us with a scheme to try to force Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi out of power; they wanted us to refuse to support IMF loans to Italy until he was gone.”

The collusion of the Italian left supported by left-leaning judges and prosecutors and international actors did finally lead to the replacement of Silvio Berlusconi’s coalition government with the League by a technical government led by a Eurocrat.

Plan A (the IMF loan) actually failed, but Plan B was successful. At the beginning of November 2011, Italy was forced into bankruptcy by the disproportionate increase in the spread between its debt securities and German debt securities. While the fundamentals had not changed, this spread rose from 171 points (1.71 percent) at the end of June 2011 to 553 points on November 9, 2011, after the G20 summit in Cannes. On June 30, 2011, Deutsche Bank suddenly sold almost all of its Italian debt securities, worth €8 billion, causing a panic effect on the markets. The question remains whether the rating agencies Fitch, Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s were simply reacting to the events when they downgraded Italy’s rating at that time or whether they knowingly fueled speculation about Italian debt. Three years after Berlusconi’s resignation, the credit spread was only 107 points despite a debt of 134 percent of GDP compared to 120 percent in 2011 and higher unemployment.

Another major factor that led to the fall of the Berlusconi government in 2011 was the defection of Gianfranco Fini, the then president of the Chamber of Deputies and number two in Silvio Berlusconi’s party, which he left in February 2011 to create his own party with a group of parliamentarians, leaving Berlusconi with a thin majority in parliament. At the time of his defection, Fini was the target of an investigation that was then closed in record time by the Public Prosecutor’s Office in Rome. According to former prosecutor Luca Palamara, who gave his recollection of events in a book entitled “Il Sistema” (“The System”) published in 2021, the association of Italian magistrates (ANM) had conducted discussions with Fini before his defection. Luca Palamara was president of ANM from 2008 to 2012 and a member of the High Council of the Judiciary (CSM) from 2014 to 2018.

[pp id=58052]

It is only last year that the Italian right finally managed to return to power under the leadership of Giorgia Meloni, with the participation of Silvio Berlusconi and Matteo Salvini, after winning the elections with an overwhelming majority.

Both the Italian prosecutors and judges and international actors like Nicolas Sarkozy, Angela Merkel, and even Jean-Claude Juncker, the then president of the Eurogroup who would later become president of the European Commission, had a common motive to oust Berlusconi’s government in 2011: After having sown chaos in Libya with France’s and Britain’s bombardment campaign that eventually led to the murder of Gaddafi by rebels that year and a civil war that is still devastating that country today, it was time for European leaders and the Italian left to open wide the doors of Italy to massive illegal immigration.

As was revealed by leaked chats between prosecutors and members of Italy’s council of the judiciary, the CSM, in 2020 many influential members of the Italian judiciary were very keen to actively promote illegal immigration and attack right-wing politicians for that purpose.